Mark S. Brodin

Boston College Law School

Let me say at the outset how truly honored I am to be on this panel with such distinguished colleagues. This is no false modesty—I’m the only one of us without their own Wikipedia page.

The last time I spoke here was at a celebration for Steve Subrin, one of our most profound thinkers about procedure and litigation, and an enormous influence on me and so many others.

Today I speak about another great role model, who has inspired generations of law students, civil rights lawyers, and even boxing fans. During my dark days as a law student at an institution that saw itself primarily as a sorting operation for Cravath and Cleary, and that viewed public interest practice as a cute pro bono hobby, a brilliant legal tactician and consummate teacher appeared with a very different message.

Michael, at the ripe old age of 32, was already a civil rights legend. I'd like to speak this morning about Michael as a teacher, my teacher. He and Phil Schrag taught the first clinical courses at a school so mired in tradition that anything other than the full-blown, Kingsfield, Socratic classroom sent some faculty into spasms.

Meltsner and Schrag would not publish their ground-breaking book, Public Interest Advocacy: Materials For Clinical Legal Education, until 1974, but already the pioneering model, melding highly sophisticated advocacy training with a social justice focus, was in operation.

In their book, they write:

Public interest practice is significantly different in style, organization, and purpose from the traditional private practitioner model. Public interest lawyers may spend their day much as other lawyers do-- interviewing, drafting, negotiating, arguing in court-- but by and large they are issue-oriented, viewing legal representation as an integral part of the efforts to make society live up to the goals that they personally regard as desirable.

Michael and Phil "rejected the notion that a good lawyer must be a hired gun, as content to help a large and powerful corporation acquire another large company as to fight for the vindication of an unlawfully imprisoned man." One of Michael's passions was (and is) challenging the civil disabilities that irrationally disqualify convicted felons from so many occupations after their release from custody. Mike’s client, world boxing champion Mohammed Ali, was only the most high-profile victim of such wrong-headed policies. I worked on one such test case under Michael's supervision, building it from the ground up. The client had served his time, only to be blocked at every effort to secure employment.

Any wonder why the recidivism rate is so high?

In the spring semester, I worked under Phil's supervision on a federal complaint challenging the citizenship requirement for admission to the bar, another impediment to employment and an issue that later went to the Supreme Court.

It is now widely accepted that law students can learn invaluable lessons from such real-life experiences, perhaps even more than in the classroom. But it took pioneers like Michael and Phil and Gary Bellow to make this case to a very stodgy establishment, still much in the thrall of Christopher Columbus Langdell.

Today, no self-respecting law school can possibly claim to educate future lawyers without a robust set of clinical offerings—now called “experiential learning.” But there was so much more to the Meltsner experience than education in the art of lawyering. Many of my classmates felt we were viewed as a necessary evil at Columbia—the walking tuition dollars that allowed faculty to do their consulting downtown, and to pursue their scholarship. Faculty offices were upstairs, somewhere, and even if you found your way to Oz, the doors were usually closed.

Old school formality was the prime decor at 116th & Amsterdam.

Some of the nearly all-male faculty came and went in town cars that would transport them to the enclaves "in the Canyon (Wall Street)." Michael arrived at school on his motorcycle, helmet under arm, al la C. Wright Mills, the great radical sociologist at Columbia.

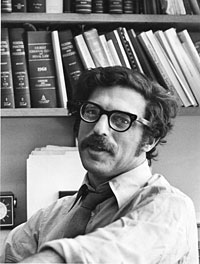

Michael Meltsner, circa 1970. Courtesy Michael Meltsner.

When Mike invited the class to his charming apartment on Riverside Drive, Carol King was playing on the stereo, and Michael engaged each of us in real conversation—what were our interests, our plans, our backgrounds? He stood out, in short, as welcoming, authentic, and indeed a very hip guy—he was one of us!

But alas, while my classmates and I were still trying to figure out the difference between holding and dictum (and, more importantly, why we cared about the difference between holding and dictum), Michael Meltsner had already been part of that incredible circle around Thurgood Marshall that so transformed our society, and established The Law, and dedicated lawyers, as the engine of profound social change.

Derrick Bell, Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley, Robert Carter, James Nabrit. Michael joined this group at the Legal Defense Fund in 1961, as only it’s 6th member. Now 1961 was certainly one of those pivotal years— The beginning of JFK's vibrant New Frontier. The first freedom riders reached the South. The first lunch counter protestors gained national attention. Joseph Heller's masterpiece Catch 22 appeared, giving voice to those disaffected by the darker sides of bureaucracy and the military mindset.

At the LDF Mike immersed himself in the noble effort to turn Brown v. Board into a reality, not just an aspiration, trying school desegregation cases in the south, as well as representing civil rights protestors caught up in the former Confederacy’s Kafkaesque criminal justice system. This was, in the words of Jack Greenberg, “the era of trench warfare.” The work was invigorating, but often frustrating, and sometimes downright dangerous. This boy from the West Side of Manhattan found himself pulled over by local sheriffs on dark rural roads, right out of the classic film “In The Heat Of The Night”.

Called a Communist, an outside agitator, and a race-mixer by the local whites. Spat upon by an elderly white man in the South Carolina Federal Courthouse. And, at the same time, having to maneuver through the sharp divisions exploding in the Black community itself. Martin Luther King Jr. versus Malcolm. Those seeking integration versus those seeking a separate nationalist identity.

Early on at the LDF, Mike read hundreds of prisoner’s letters, and pursued those cases that had a chance of law reform. In one, a Tennessee man had been convicted based on statements elicited by newspaper reporters sent into his cell to trick him into repeating incriminating statements that were not admissible from the police interrogation. One wonders where the self-imposed limits of prosecutorial ethics are. Mike secured a summary reversal by the Supreme Court.

The profound injustices of the justice system jumped off the handwritten pages of these inmates pleading for assistance. This led Michael and the LDF into its campaign against the death penalty, in all too many cases the product of racial decision-making from arrest to execution.

I graduated law school in 1972, the same year Michael and Tony Amsterdam won Furman v. Georgia, the landmark decision representing the high point in the struggle against state-sanctioned killing. The Supreme Court's decision was an eye-opening indictment of the totally arbitrary and capricious operation of capital punishment, and halted executions for several years.

Now, I have to note—it is all the more the remarkable that, as a graduate of both Oberlin College and the Yale Law School, Michael was able to accomplish all this without any formal education. Looking back on those years, Mike would recall:

Despite the obstacles, in the movement era, civil rights activists floated on waves of hope. We were primed to act, and act often, achieving positive, if also limited, results. We had a feeling of slow but inevitable progress, built on confidence in the justice of what we were doing, reinforced by widespread public support and the belief that a majority of federal judges agreed with us.

"Mine [Michael later mused] was an intense love story of work and workplace, a serendipitous journey through the heart of what was, for the legal profession, the very best of times."

To quote the great 20th century philosopher—Archie Bunker—“those were the days.”

Now I haven’t even touched yet on Mike’s other career, as a novelist and playwright. Mike is not only an avid consumer of great literature, but a very talented writer in his own right. It was Michael who introduced me to John Updike’s Rabbit series, while his colleagues were urging us to read more Prosser.

Mike asked me to moderate a panel discussion after the premier performance of his very powerful play, In Our Name, a grim portrayal of the on-going moral obscenity that is Guantanamo. The play anticipates the tragic consequences of non-accountability that we live with today. If you have the chance, you must see it. But don’t sit in the front row, as I did. One of the inmates gets waterboarded in the second act. That turned out to be the only speaking engagement I’ve done dripping wet.

Mike’s 1979 novel Short Takes is incredibly evocative of coming to age in Manhattan in the era before the 1% displaced so much of the cultural charm of the city. His scenes of the Catskill Mountains brought me right back to my youthful days as a bottom-of-the-food-chain musician, working at bottom-of-the-food-chain hotels.

On a personal note, it was Professor Meltsner who understood why I turned down more prestigious Circuit Court clerkships and opted instead for a federal district court—he told me that was where law reform was going on, and he was dead-on.

It was Michael who understood why I accepted a clerkship in Burlington, Vermont (of all places) rather than the Southern District, where “the real action was.”

It was Professor Meltsner who understood why I would turn down an offer from the prestigious Sullivan & Cromwell, and later end up in the public defender’s office here in Boston. (By the way, my civil procedure professor and mentor was so distressed by this decision that he summarily dispensed with my services as his research assistant, and traded me to a brand new Columbia professor named Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

Mike’s colleagues just shook their heads in sympathy for all my crazy, career-ending choices, but he was with me all the way. We in this room all owe so much to Michael. He inspired me to a career as a civil rights lawyer here in Boston during the turbulent 1970s (with my great friend Alan Rom, sitting here today), and then as teacher and scholar in the field, preparing the next generation of socially-committed lawyers.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. used to advise his young colleagues that to achieve greatness in the legal profession, one must immerse oneself in the agonies of their times. Today we justly celebrate one such remarkable person.