Introduction

On July 28, 2022, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 76/300 recognizing the human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.1 This is a historic step forward for environmental rights, but it is not the end point. Rather, this signals a new phase of international engagement, with more focused debates, more international consultations, and fierce, new legal actions to promote an effective “rights-based approach” to the crises of climate catastrophes, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

This guide was created to assist the scholars, advocates, and activists who are carrying this work forward and engaging with the further development and implementation of the human right to a healthy environment. Following this Introduction, Section I provides background on the development and recognition of this important new right. Section II addresses the challenges associated with defining the right to a healthy environment. Section III outlines human rights principles and standards related to the right. Section IV provides an annotated bibliography of resources that will support further research on, and development of, the right.

I. Recognizing the Human Right to a Healthy Environment

The UNGA resolution reflects the widespread awareness of environmental issues, as a majority of people see climate change as a very serious concern and deplore the lack of governmental action to address it.2 As noted by John Knox, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, “[w]ere the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to be drafted today, it is hard to imagine that it would fail to include the right to a healthy environment, a right so essential to human well-being and so widely recognized.”3

Growing public pressure on governments and leaders certainly influenced the UNGA’s recognition of the right to a healthy environment. But reaching this level of environmental awareness required decades of mobilization.

The initial emergence of the right to a healthy environment corresponded with the beginning of the environmental movement in the late 1960s.4 Almost a decade later, Portugal and Spain were the first two countries to adopt a right to a healthy environment in their constitutions, in 19765 and 1978,6 respectively. International declarations related to environmental issues, such as the Stockholm Declaration7and the Rio Declaration,8 followed in the two next decades, reflecting the growing awareness of the relationship between human rights and the environment.

Since the 1990s, a more fine-grained understanding of climate change and its consequences, as publicized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), spurred awareness of the impact of climate change on human rights.9 For example, after examining the disparate impacts of climate change on minority communities, the IPPC shifted its policy focus to climate justice.10

At the same time, extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense, with more severe consequences. Pollution-induced diseases cause one in six deaths in the world.11 Two billion people lack access to safely managed water, a shortage that will only become more acute as the climate changes.12 Controlling pollution and providing access to safe water are just two examples of the many climate-related challenges that lie ahead. An internationally recognized right to a healthy environment will be a critical tool for meeting these challenges.

Over time, most countries have responded to the environmental movement by progressively integrating environmental rights into law.13 One hundred fifty-six countries have now adopted a right to a healthy environment, and they have done so in a variety of ways: by including the right in national constitutions and legislation, by acknowledging the right in judicial decisions, and by signing international treaties that include the right.14

This international recognition of the right to a healthy environment is especially promising in three respects. First, some studies have found that the recognition of the right in national constitutions has contributed to improved implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, increased public participation in environmental governance, enhancement of laws related to environmental education, and increased health of people and ecosystems.15 The full recognition of this right by the UN could set the stage for more robust implementation and stronger enforcement at the national level.

Second, the international level is a pertinent forum to address issues that are not purely national. Transboundary pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, imported deforestation, and other environmental issues are not subject to national boundaries, but often reveal relations of power between nations – from neighboring nations polluting their neighbor’s territory, to exploitative relationships between the Global North and the Global South.16 A legal tool recognizing the right to a healthy environment could thus engage with international dynamics that fall outside of most national legal instruments.

Third, the recognition of the human right to a healthy environment could enable right-holders to hold governments accountable for breach of their international obligations, empowering citizens who find their human rights disrespected. This point is particularly relevant to climate justice, when indigenous peoples, women, persons with disabilities, children, persons living in poverty, and religious, national, ethnic, or linguistic minorities are the most affected by environmental harms but often do not have the legal means to seek redress.17 Recognizing a human right to a healthy environment could alleviate some legal barriers and give citizens leverage when challenging governments or companies responsible for breaching their right to a healthy environment.

Understanding the new human right to a healthy environment will involve challenges. First, the nature and scope of the new right are unclear. The UNGA resolution recognizing the right does not provide a detailed account of the right’s definition and scope. Furthermore, the many of countries that have enshrined a right to a healthy environment in their constitutions and laws have described the right in variety of ways, and these different versions of the right have been subject to country-specific interpretations. Work will therefore be required to achieve an international consensus on the meaning of the new right. Second, researching the right to a healthy environment involves navigating various jurisdictions (international, regional, national, and subnational) and instruments (constitutions, legislation, judicial decisions, and treaties). The undefined nature of the right and the complexity of the research associated with the right will make understanding the practical dimensions of the right particularly demanding.

II. Defining the Right to a Healthy Environment

Defining the right to a healthy environment will involve developing richer accounts of the nature of the right, the purpose of the right, the scope of the right, and the State obligations that flow from the right.

Though a version of the right to a healthy environment is recognized by eighty percent of UN member States, these countries do not all use the phrase “healthy environment” when enshrining the right in their domestic laws.18 International declarations recognizing early environmental rights also use alternative formulations19 that range from the protection of “an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity of well-being,”20 to the protection of “a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature,”21 the guarantee of an “ecologically balanced environment,”22 and a “balanced and healthful ecology.”23 Although these various expressions make it more complicated to identify a single definition of the right to a healthy environment, they share a focus on the interrelation between human life and the environment and an awareness of the importance of ensuring that the environment be healthy enough to support human life. The expression used by the UNGA, “the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment,” is broad and flexible; 24 the meanings of its key terms will be developed over time.

In addition to developing a more detailed understanding of the right itself, the international human rights community will be engaged in negotiating competing understandings of the purpose of the right: the anthropocentric view versus the ecocentric view.25

The anthropocentric view of the right focuses on the idea that the integrity of the environment is indispensable for supporting healthy humans.26 In this vein, scholars have defined the right to a healthy environment as the “human right to live in an environment of such a minimum quality as to allow for the realization of a life of dignity and well-being,”27 or as “the right to an ecologically balanced and sustainable environment which permits healthy living for all of its inhabitants.”28 These definitions are anthropocentric as they focus on a qualitative environment that would enable human life to thrive, expressing a utilitarian vision of the right to a healthy environment. The environment is not considered as an object to protect in itself, but as a commodity supporting human subjects.

The ecocentric view of the right provides a broader understanding of the interrelation between humans and their environment; a healthy environment is defined as the health of an ecosystem, independently of its usefulness for human life.29 The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) seems to have adopted an ecocentric definition of the right to a healthy environment, stating it “protects nature and the environment, not only because of the benefits they provide to humanity or the effects that their degradation may have on other human rights, such as health, life or personal integrity, but because of their importance to the other living organisms with which we share the planet that also merit protection in their own right.”30

Both the anthropocentric and ecocentric understandings of the right to a healthy environment have been enshrined in national constitutions and regional agreements, and adopted by courts. The UNGA definition of the right to a healthy environment does not provide clarification of the anthropocentric and ecocentric dimensions of the right. Ultimately, since the environment impacts humans, and vice versa, the difference between the anthropocentric and the ecocentric visions of the right to a healthy environment may be more a matter of degree than of substance.31

The scope of the right to a healthy environment is also a matter of concern when defining this right. The right to a healthy environment is understood as both an individual and collective right; it is formulated as an individual right in most national constitutions, and as either an individual or a collective right in regional agreements.32 For instance, the African Charter on Human Rights provides for a collective right to a healthy environment,33 whereas the IACtHR defines the right to a healthy environment as “a right that has both individual and also collective connotations.”34 The Draft proposal of an additional protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), concerning “the right to a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment”35 defines it as “the right of present and future generations to live in a non-degraded, viable and decent environment,”36 adopting a view similar to that of the IACtHR. The collective connotation of the right to a healthy environment encompasses both current groups of people (in the case of the African Charter of Human Rights) and future generations (as interpreted by the American Court of Human Rights and by the Draft amendment to the ECHR). Since the scope of the right has not been clearly stated in international legal documents, the collective and individual dimensions of the right recognized by the UNGA are still unclear.

A key aspect of the right to a healthy environment is that it creates State obligations. It is therefore a “claim right” insofar as it imposes “positive obligation[s] of third parties towards the right holder”37 in contrast to “liberty rights” that establish freedom or permission to act. In other words, the right to a healthy environment enables individuals to assert their right towards States that would infringe on it, rather than merely conferring the right to live in a healthy environment without any legal avenue to enforce that right.

The IACtHR listed the five State obligations encompassed by the right to a healthy environment:

- guaranteeing everyone, without any discrimination, a healthy environment in which to live;

- guaranteeing everyone, without any discrimination, basic public services;

- promoting environmental protection;

- promoting environmental conservation; and

- promoting improvement of the environment.38

These obligations give an idea of the kind of new duties that could be imposed on States through the UN’s recognition of the right to a healthy environment. For now, such obligations are not explicitly in place through the UNGA Resolution on the right to a healthy environment. Rather, the Resolution calls for the full implementation of existing multilateral environmental agreements. In articulating the State obligations that flow from the right to a healthy environment, it will be important to recognize the substantive and procedural components of the right. Substantive components include the following:39

- The first component is the right to clean air, which includes seven State obligations related to monitoring and assessing pollution sources, making information publicly available, establishing air quality information, and developing, implementing, and evaluating air quality action plans.40

- The second substantive component is the right to a safe climate. It is implemented by states enacting climate framework legislation or enshrining provisions related to climate change responsibility in their Constitutions.41

- The third substantive component of the right to a healthy environment is access to safe water and adequate sanitation, which are themselves independent human rights. The optimal implementation of these rights requires a clear articulation in a State’s legal framework guaranteeing availability; physical accessibility; affordability; quality and safety; and accessibility.42

- The fourth component is the guarantee of a non-toxic environment in which to live, work, and play. This element is usually implemented by States that ratify global treaties prohibiting, encouraging the phasing-out of, or limiting certain substances.43

- The fifth component is the right to healthy and sustainably produced food, which implies favoring organic agriculture, agroecological farming, land restoration, and the decrease in meat production and consumption.44

- The sixth and final substantive element is the guarantee of healthy ecosystems and biodiversity, which implies States’ ratification of international treaties establishing norms for biodiversity protection and/or adopting constitutional provisions protecting wildlife and nature.45

The procedural components of the right to a healthy environment are also critical, as without procedural rights, substantive rights cannot be enforced. Procedural rights related to the human right to a healthy environment include three main elements, all of which are common components of human rights:

- The first element is access to environmental information. This is implemented by nation states that, inter alia, create websites providing environmental information, publish national reports, and ensure the affordability of access to this information. Some countries guarantee the right to environmental information in their constitutions.46

- The second procedural element of the right to a healthy environment is the right to public participation in environmental decision-making. This requires “ensuring broad, inclusive and gender-sensitive public participation”47 and is usually implemented by the enactment of constitutional provisions, laws, or protocols.48

- The third and final element of procedural rights is access to justice and effective remedies. A common implementation of this element is the recognition that individuals and non-governmental organizations have the standing to bring lawsuits based on the violation of environmental rights.49

Additional obligations also exist towards individuals in vulnerable situations as they may be “unusually susceptible to certain types of environmental harm or because they are denied their human rights, or both.”50 Vulnerable populations include “women, children, persons living in poverty, […] indigenous peoples […], older persons, persons with disabilities, national, ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities and displaced persons.”51

I. Human Rights Principles and Standards Regarding the Right to a Healthy Environment

The right to a healthy environment has not previously been explicitly recognized in international human rights instruments. The so-called International Bill of Human Rights52 includes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,53 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),54 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).55 These instruments were drafted in the post-war period, before the environmental movement of the late 1960s led to an increased awareness of environmental issues.56

Despite this lack of explicit recognition in the most influential international human rights instruments, the “greening of human rights” theory argues that the right to a healthy environment has been implicitly recognized in fundamental human rights, civil and political rights, economic, social, and cultural rights, and children’s rights.57

For example, the Human Rights Committee recognized the impact of environmental hazards in its General Comment No. 26 concerning the ICCPR’s right to life:58 “Environmental degradation, climate change and unsustainable development constitute some of the most pressing and serious threats to the ability of present and future generations to enjoy the right to life.”59 The Committee thus seems to implicitly accept that the right to life, which is a civil and political right, encompasses environmental protection. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has adopted the same reasoning to enforce the right to a healthy environment.60

In the sphere of economic, social, and cultural norms, several rights have been interpreted to include environmental concerns. The right to an adequate standard of living provided in Article 11(1) of the ICESCR includes the rights to adequate food, housing, and safe water and sanitation.61 The interpretation of this right also includes the consideration of environmental hazards. General Comment No. 12 on the right to adequate food details the normative content of Article 11(1) and Article 11 (2) of the ICESCR regarding the adequacy and sustainability of food availability and access: “The notion of sustainability is intrinsically linked to the notion of adequate food or food security, implying food being accessible for both present and future generations. The precise meaning of ‘adequacy’ is to a large extent determined by prevailing social, economic, cultural, climatic, ecological and other conditions, while ‘sustainability’ incorporates the notion of long-term availability and accessibility.”62

Likewise, UN Special Rapporteurs have been responsible for some of the “greening” of human rights.63 The Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation recently published a two-part thematic report on climate change and the human rights to water and sanitation.64 The Special Rapporteur on adequate housing published a Special Report focused on the right to non-discrimination, including an analysis of the impact of climate change on several types of communities.65

Another economic, social, and cultural right that has been “greened” is the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, recognized under Article 12 of the ICECSR.66 General Comment No. 14 issued by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights indicates that the right to a healthy environment is included in the right to the highest attainable standard of health: the “drafting history and the express wording of article 12.2 acknowledge that the right to health … extends to the underlying determinants of health, such as … a healthy environment.”67

Greening of human rights also emerges from the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which mentions the risk of environmental pollution.68 According to the CRC, States must take appropriate measures to ensure the implementation of the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health.69 States must likewise take appropriate measures to “combat disease and malnutrition, including within the framework of primary health care, … through the provision of adequate nutritious foods and clean drinking-water, taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution.”70 In General Comment No. 7 on the implementation of rights in early childhood, environmental concerns are discussed under the right to life, survival, and development of the child.71 The Committee on the Rights of the Child reminds States that this right can be holistically implemented only through the enforcement of, among other things, “a healthy and safe environment.”72 These provisions are, however, applicable only to children and are thus limited in their scope.

Parallel to, but independent of, the greening of human rights, environmental human rights have been developing on the international stage, notably through international declarations progressively recognizing these rights.

The first major international declaration recognizing environmental rights is the Stockholm Declaration (1972).73 The first principle of the Declaration states, “Man has the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being, and he bears a solemn responsibility to protect and improve the environment for present and future generations.”74 Coming only a few years after the environmental movement first gathered steam in the 1960s, this principle is already close to the contemporary understanding of the right to a healthy environment.

Fifteen years after the Stockholm Declaration, in 1987, the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development published an overview that restated, in a similar language, the concepts introduced in the first Principle of the Stockholm Declaration.75 These two documents thus introduced environmental rights as human rights, though without giving a precise definition.

In the ensuing decades, international declarations on environmental human rights focused on procedural rights. Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992) identified three new fundamental rights related to procedural environmental rights: access to information, access to public participation, and access to justice.76 These procedural rights were reinforced in 2010 by the Bali Guidelines,77 which provided voluntary guidelines for the implementation of the rights stated under Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration.78 In 2012, the UN General Assembly adopted the “The Future We Want” Resolution, which reaffirms identical principles79 and emphasizes their development at the regional and subnational levels.80 These soft law instruments provide attest to the increasing awareness surrounding environmental human rights, eventually leading to the development of the idea of the right to a healthy environment.

The bibliographic materials below build on the exposition of the international evolution of environmental rights. Part A provides selected HRC (Human Rights Council) publications highlighting the gradual change in the Council’s position on the adoption of a right to a healthy environment. Part B lists selected reports from Special Procedures that assess the need for the adoption of this right. Part C provides information on the HRC’s adoption of Resolution 48/13, which recognized the human right to a healthy environment, and the UNGA’s subsequent recognition of the right. Part D provides one example of the ways in which the resolution is impacting other rights. Annex I describes international bodies that are working on the right to a healthy environment.

A. Human Rights Council Publications Highlighting the Interconnection Between Environmental Rights and Human Rights: Paving the Way to the Explicit Recognition of the Right to a Clean, Healthy, and Sustainable Environment Publications appearing in this section highlight the evolution of the HRC’s engagement with the right to a healthy environment. This U.N. body (which succeeded the U.N. Commission on Human Rights in 2006) first recognized the link between environmental protection and human rights, and then expanded its understanding by appointing Special Rapporteurs and considering the right to a healthy environment as a human right.

Commission Hum. Rts., Res. 2005/60, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/RES/2005/60 (Apr. 5, 2005)

The resolution adopted by the UN Commission on Human Rights prior to the creation of the HRC in 2006 recognized the link between human rights, environmental protection, and sustainable development. The Commission also observed that “environmental damage, including that caused by natural circumstances or disasters, can have potentially negative effects on the enjoyment of human rights and a healthy life and a healthy environment.”81 Subsequent HRC actions built on this foundation.82

This report recognizes that even if the universal human rights treaties do not mention the right to a safe and healthy environment, there is an intrinsic link between this right and “the realization of a range of human rights, such as the right to life, to health, to food, to water, and housing.”83 The right to survival and early development also includes the right to healthy and safe environment.84

This report details three theoretical approaches to the relationship between human rights and the environment.85 It also identifies the call for the recognition of a human right to a healthy environment and notes alternative views that such a right already exists de facto.86

Hum. Rts. Council, Res. 19/10, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/19/10 (Apr. 19, 2012)

This resolution appointed John Knox as the first independent expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.87 The HRC opines that the right to a healthy environment requires further study and clarification.

Hum. Rts. Council, Res. 25/21, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/25/21 (Apr. 15, 2014)

This resolution recognizes that “human rights law sets out certain obligations on States that are relevant to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment.”88 The resolution urges States to comply with their human rights obligations.89

Hum Rts. Council, Res. 28/21, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/28/11 (Apr. 7, 2015)

This resolution extends John Knox’s mandate, transitioning the position from Independent Expert to Special Rapporteur on the same subject.90 This change in title reflects the growing weight that the HRC attached to the right to a healthy environment.

Hum Rts. Council, Res. 31/8, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/31/8 (Mar. 23, 2016)

This resolution encourages States to “adopt an effective normative framework for the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment”91 and to “address compliance with human rights obligations and commitments relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment in the framework of human rights mechanisms.”92

B. Reports of the Special Procedures on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Clean, Healthy, and Sustainable Environment: Evaluating the Need for the Recognition of the Right to a Healthy Environment

This part includes selected reports from the Independent Expert and Special Rapporteurs (collectively, Special Procedures) on the right to a healthy environment showing the evolution of the conceptualization of the right. These reports range from assessing the need, the scope, and the definition of the right to a healthy environment, to defining in substantial detail the right to a healthy environment and calling for its recognition by the UN General Assembly.

This first report by John Knox as Independent Expert details the evolution of environmental rights, including the right to a healthy environment; identifies human rights that are vulnerable to environmental harms; and underscores vital human rights for environmental policymaking. The report also frames the right to a healthy environment and defines the areas where there is a need for conceptual clarification.

This is the first report of John Knox submitted to the General Assembly as a Special Rapporteur. He recommends that the General Assembly recognize the human right to a healthy environment by including it in a global instrument93 such as a new international treaty94 or by developing “an additional protocol to an existing human rights treaty”,95 or by adopting a resolution on the right to a healthy environment.96 The report also highlights evidence showing that adopting a right to a healthy environment contributes to healthier people and healthier ecosystems.97

This report highlights that the right to a healthy environment has been recognized by most States, either domestically in their constitution or legislation, or through regional human rights treaties to which they are parties. In a second part, the report focuses on human rights obligations relating to the right to breathe clean air as a substantive element of the right to a healthy environment.

This report sets out good practices in the implementation of a right to a healthy environment. It is divided into three main sections: (1) good practices implemented by States that have recognized the right to a healthy environment, (2) good practices regarding the procedural elements of the right to a healthy environment, and (3) good practices regarding the substantive elements of this right.

This report focuses on the right to a non-toxic environment, which is a substantive element of the right to a healthy environment.98 The report details the impact of pervasive pollution and toxic contamination on people and the planet and focuses on environmental injustices and sacrifice zones, i.e., areas where residents live in close proximity to pollutants. A final section details the procedural, substantive, and special obligations related to pervasive pollution and toxic substances.

C. UN Bodies Formally Recognize the Human Right to a Healthy Environment The HRC's evolution on the right to a healthy environment, resulting from reports from Special Procedures, and numerous calls from countries, NGOs, and UN bodies, led to the HRC’s recognition of the right to a healthy environment as a human right in October 2021, and the UNGA’s recognition of the right in July 2022. Hm. Rts. Council, The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, A/HRC/Res/48/13 (Oct. 8, 2021)

In this resolution, the Human Rights Council “recognizes the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right that is important for the enjoyment of human rights.”99

UN General Assembly, The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, A/RES/76/300 (July 28, 2022)

Building on the earlier HRC resolution, the UN General Assembly voted 161 in favor, with none opposed, and eight abstentions, to recognize the human right to a healthy environment.

D. Regarding the Right of the Child to a Healthy Environment

Following the HRC’s recognition of the right to a healthy environment, the Committee on the Rights of the Child began preparing a General Comment that could include children’s rights to a healthy environment, further defining the right to a healthy environment.

This concept note provides insight into the scope and objectives of the forthcoming General Comment No. 26. It also recalls the impact of climate change on children.

Annotated Bibliography

A. Adjudications by UN Bodies Relevant to the Right to a Healthy Environment

This part sets out cases considered by UN bodies related to the right to a healthy environment. As the right to a healthy environment has just recently been recognized by the UN General Assembly, there is no case law directly addressing this right. Cases mentioned below raised arguments referencing the substantive and procedural aspects of the right to a healthy environment, with varying results as to recognition of the right.

This case examined whether the heavy spraying of toxic agrochemicals on the industrial farms in the area where the plaintiffs live and its consequences amount to a violation of their right to privacy and family life, a violation of their right to life and physical integrity, and a violation of their right to an effective remedy. The claimants did not claim a violation of their right to a healthy environment but argued that this right is included in the right to life as per General Comment No. 36.100 The Committee concluded that environmental harm poses a reasonable threat to the plaintiffs’ lives and ordered Paraguay to provide an effective remedy but did not rule on whether environmental harm amounts to a violation of the right to a healthy environment.

Sacchi v. Argentina, Com. Rts. Child, Dec. 107/2019, U.N. Doc. CRC/C/88/D/107/2019 (Nov. 11, 2019)

In this case, the Committee considered whether the State party, through its contributions to climate change, failed to take the necessary preventative and precautionary measures to protect and fulfill children's rights to life, health, and culture. The Committee accepted the plaintiffs’ argument, finding that Argentina has an extraterritorial responsibility related to the harmful effects of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted within its borders and impacting children outside its borders. The Committee also found that plaintiffs were victims of foreseeable harm related to CO2 emissions. The Committee considered the appropriate test for jurisdiction and adopted the one enunciated by the IACtHR when establishing whether countries have extraterritorial responsibilities related to CO2 emissions, in its Advisory Opinion recognizing the right to a healthy environment.101 The Committee also examined the causal link between the alleged harms and the State’s actions and omissions. Ultimately, the Committee dismissed the case on the ground that domestic remedies had not been exhausted.

B. Regional Human Rights Agreements and Litigation on the Right to a Healthy Environment

In this section, Subpart (i) examines relevant regional human rights agreements that recognize, implicitly or explicitly, the right to a healthy environment. Despite superficial regional uniformity of the recognition of this right, situations are diverse and vary with a State’s domestic jurisprudence, the individual or collective dimension of the right to a healthy environment, and the lack of the enforceability of some agreements. Subpart (ii) discusses cases from regional human rights tribunals that enforce the right to a healthy environment.

i. Regional Human Rights Agreements and the Right to a Healthy Environment

European Convention on Human Rights, Sept. 3, 1953

The ECHR does not provide a right to a healthy environment, yet its jurisprudence uses other fundamental rights to recognize the right (such as the right to life [Article 2] or the right to private and family life [Article 8]), following the “greening of human rights” theory. A recommendation to draft an additional protocol to the ECHR concerning the right to a healthy environment was adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2009102 but was rejected by the Committee of Ministers in 2010.103 A new resolution to anchor the right to a healthy environment was subsequently adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly in September 2021, reviving the discussion about drafting an additional protocol to the ECHR on the right to a healthy environment.104

The Aarhus Convention is a treaty developed by the UN Economic Commission for Europe and signed by a majority of European and Central Asian countries. The Convention provides for environmental procedural rights such as public access to environmental information and opportunities for participation. The Preamble and the first Article of the Convention can be read to include a right to live in a healthy environment, but these provisions are not enforceable. The Convention thus does not grant any substantive rights regarding a healthy environment.

American Convention on Human Rights, Nov. 22, 1969

The American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) does not explicitly include a right to a healthy environment but has recognized this right through an expansive reading of fundamental rights protected by the Convention, notably Article 26, providing the obligation of States to ensure “integral development for their peoples.”

Protocol of San Salvador to the American Convention on Human Rights, Nov. 17, 1988 The Protocol of San Salvador, an additional protocol to the ACHR addressing economic, social, and cultural rights, explicitly provides a right to a healthy environment: “1. Everyone shall have the right to live in a healthy environment and to have access to basic public services. 2. The States Parties shall promote the protection, preservation, and improvement of the environment.” (Article 11). The Protocol entered into force in 1999.

The Escazú Agreement aims to implement environmental procedural rights in Latin American and the Caribbean in the same way that the Aarhus Convention does in Europe. Article 1 provides that the objective of the Agreement is to “[protect] the right of every person of present and future generations to live in a healthy environment,” yet the enforceability of this provision is still unclear. The Agreement entered into force in 2021.

African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, June 27, 1981

The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) provides a right to a healthy environment: “All peoples shall have the right to a general satisfactory environment favorable to their development.” (Article 24). The phrasing of this right is unique as it designates a group and not individuals as beneficiaries of this right.

Arab Charter on Human Rights, May 22, 2004

The Arab Charter on Human Rights provides a right to a healthy environment: “Every person has the right to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, which ensures their well-being and a decent life, including food, clothing, housing, services and the right to a healthy environment” (Article 38). Unlike the ECHR, the ACHR and the ACHPR mentioned above, this Charter is not enforceable since there is no effective enforcement mechanism provided by the Statute of the Arab Court of Human Rights enabling individual petitions to be brought to the Court.

Ass’n of Southeast Asian Nations [ASEAN] Human Rights Declaration, Nov. 18, 2012

The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD) provides a right to a healthy environment: “Every person has the right to an adequate standard of living for himself or herself and his or her family, including […] a safe, clean and sustainable environment.” (Article 28(f)). As is the case with the Arab Charter on Human Rights provision, this Article is not enforceable since no enforcement mechanism is provided for the AHRD.

ii. Cases from Regional Human Rights Tribunals Examining the Right to a Healthy Environment

a. African Commission on Human and People’s Rights

The Commission examined whether toxic pollution caused by the oil industry in Nigeria amounted to a violation of the Ogoni people’s right to a healthy environment as provided by the African Charter. The Commission held that the Nigerian Government violated the right to a healthy environment for the Ogoni people. The Commission concluded that Nigeria had to take reasonable measures to prevent pollution and ecological degradation, promote conservation, and secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources.

b. European Court of Human Rights

1. Cases based on Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (right to private and family life)

López Ostra v. Spain, App. No. 16798/90, (Dec. 9, 1994)

The ECtHR considered whether a municipality’s inaction on the nuisance caused by a waste treatment plant amounted to a violation of the plaintiff’s right to private and family life. The ECtHR held that Spain failed to establish a fair balance between the interest of the town’s economic development and the applicant’s effective enjoyment of her right to private and family life. Consequently, the ECtHR held that Spain breached Article 8 of the ECHR providing the right to private and family life.

Hatton & Others v. the United Kingdom, App. No. 36022/97, (July 8, 2003)

The ECtHR examined whether Heathrow airport traffic noises, described as “intolerable noise levels,” amounted to a violation of Article 8. The Court noted that there is no explicit right in the Convention to a clean and quiet environment, but where an individual is directly and seriously affected by noise or other pollution, an issue may arise under Article 8. The Court held that the authorities struck a fair balance within their margin of appreciation and rejected the alleged violation of Article 8.

Tătar v. Romania, App. No. 657021/01, (Jan. 27, 2009)105

The ECtHR examined whether Romania’s failure to take appropriate measures to protect the health of the population and the environment — arising from the pollution of a mining corporation — constitutes negligence leading to a breach of Article 8. The Court observed that despite the absence of a causal probability, in this case, the existence of a serious and substantial risk to the health and well-being of the applicants placed a positive obligation on the State to adopt reasonable and adequate measures to protect the rights of the people concerned. The ECtHR held that Romanian authorities violated the right to private and family life and the right of the people concerned to enjoy a healthy and protected environment as provided in Romanian law.

Flamenbaum & Others v. France, App. No. 3675/04 and No. 23264/04, (Dec. 13, 2012) 106

The ECtHR examined whether the development of the Deauville-Saint-Gatien airdrome would amount to a violation of Article 8 due to the increase of noise disturbances that the development of the airdrome would impose on the airport’s neighbors. The Court reaffirmed that, while the Convention does not expressly recognize a right to a healthy and quiet environment, where a person is directly and seriously affected by noise or other forms of pollution, Article 8 of the Convention may support a claim. The Court nevertheless dismissed the case on the ground that the project conformed to French law and that the infrastructure would be of public use.

2. Cases based on Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (right to life)

Öneryildiz v. Turkey, App. No. 48939/99, (Nov. 30, 2004)

The Court examined whether the Turkish authorities had been negligent in failing to take appropriate measures regarding a fatal accident that occurred at the Ümraniye municipal dump, which was operated under the authorities’ control. The plaintiffs alleged a violation of their right to life. The Court determined that the right to life included the right to be protected against risks associated with industrial activities which are inherently dangerous, such as waste collection sites. The Court held that Turkish authorities violated the right to life in its procedural aspect by failing to take affirmative steps to provide adequate protection to safeguard the right to life and deter similar conduct in the future.

c. Inter-American Court and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

This advisory opinion was requested by Colombia and focused on the interpretation of the ACHR regarding state obligations concerning the environment, the right to life and personal integrity. The Court upheld, for the first time, the right to a healthy environment, relying on Article 26 of the ACHR and Article 11 of the San Salvador Protocol. Spelling out the consequences of this recognition, the Court detailed the state obligations related to environmental harm, including cross-border harm.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights examined a petition for precautionary measures in the case of contamination of the Santiago River and the harm it caused nearby residents. The contamination was caused by exposure to pollutants flowing through the river, used for agricultural purposes and vaporized in the air. The Commission granted the petition and requested that Mexico adopt necessary measures to stop the contamination, as this pollution affected the right to a healthy environment of the inhabitants.

This case is the first case involving litigation between two parties in which the IACtHR ruled on the right to a healthy environment. The plaintiffs argued that the environmental degradation of the territory, due to over-grazing by cattle, illegal logging of the forests, and the fences put up by ranching families breached their right to a healthy environment. The Court specified the scope of the obligations falling under the right to a healthy environment: States have the obligation to respect this right and to ensure its implementation by preventing its violations, including in private spheres. Thus, States must take legal, political, administrative, and cultural measures to ensure the respect of human rights. The Court found that Argentina had violated the right to a healthy environment of the plaintiffs’ indigenous communities.

In a case in which children’s blood lead levels were found to be far above the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, the IACHR examined whether Peru failed to respect its obligations under the right to a healthy environment by allowing a state-owned metallurgical complex to emit pollution that severely impacted the health of La Oroya’s inhabitants. The Commission held that the Government had prioritized the economic benefits from the complex over the enforcement of domestic environmental regulations. The Commission found that Peru failed to comply with its obligations regarding the right to a life with dignity, personal integrity, fair trial, access to information on environmental issues, the rights of the child, the rights to public participation, judicial protection, and health and a healthy environment. The Commission filed the case against Peru with the IACtHR and asked the Court to order Peru to implement appropriate reparation measures.

C. National Laws and Litigation on the Right to a Healthy Environment

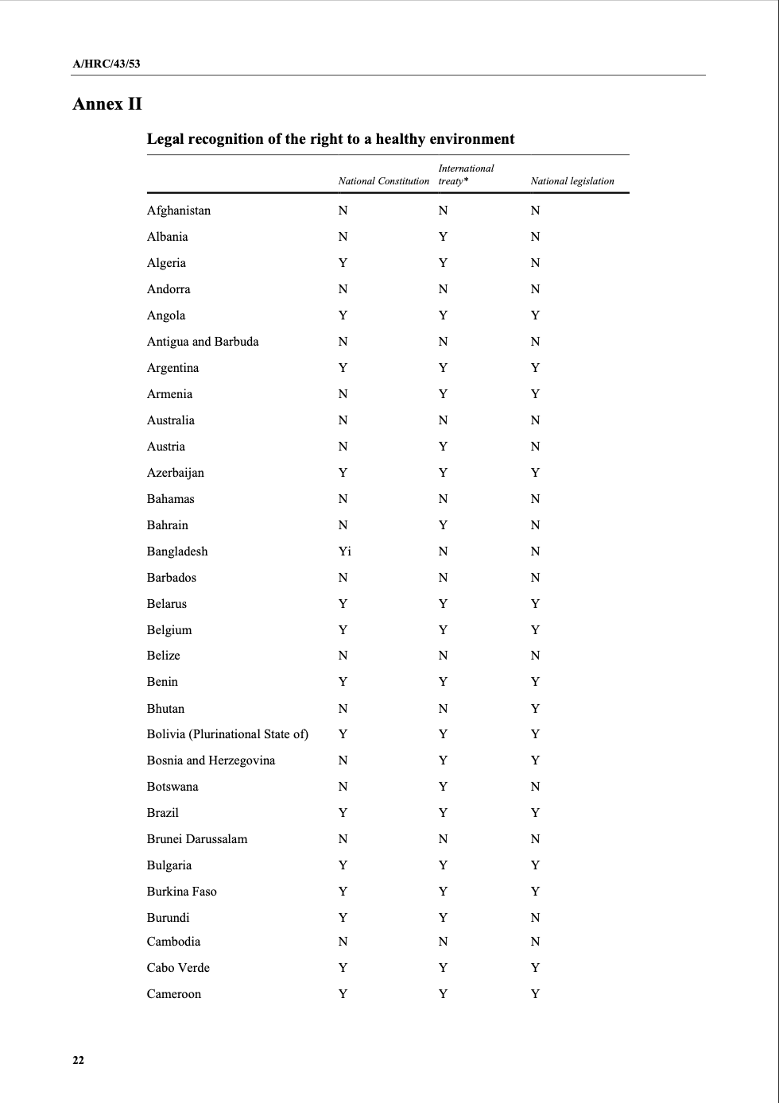

This part focuses on the domestic legal aspects of the right to a healthy environment. Most countries now recognize the right to a healthy environment: more than 80% of Member States of the United Nations, or 156 out of 193 countries, recognize this right, according to the latest counts.107 The table summarizing the legal recognition of the right to a healthy environment, reproduced in annex II, notes whether such recognition exists in each country’s national constitution, international treaty, and/or national legislation.

Subpart (i) provides examples of the right to a healthy environment in national constitutions. The selections are ordered chronologically, illustrating the evolution and normalization of the recognition of the right to a healthy environment. Selected provisions highlight the diversity of countries recognizing this right, as well as the differences in phrasing, the provision’s place within the Constitution, and duties imposed on the State. Subpart (ii) provides examples of cases ruling on the right to a healthy environment (or recognizing this right under other fundamental rights). These cases illustrate challenges related to enforcing the right to a healthy environment. In some instances, cases are dismissed, either because of a lack of standing, or because a constitutional provision is not justiciable. In other instances, cases are not given precedential weight. Despite these issues, these cases highlight the diversity of arguments and interpretations used by petitioners and Courts when examining the right to a healthy environment.

i. National Laws Providing for a Right to a Healthy Environment

Constituição da República Portuguesa [Constitution] [C.R.P.] (1976), art. 66108

Portugal was the first country to enshrine the right to a healthy environment in its Constitution in 1976. Article 66 of the Portuguese Constitution provides:

- Everyone shall possess the right to a healthy and ecologically balanced human living environment and the duty to defend it.

- In order to ensure the enjoyment of the right to the environment within an overall framework of sustainable development, acting via appropriate bodies and with the involvement and participation of citizens, the state shall be charged with:

- Preventing and controlling pollution and its effects and the harmful forms of erosion;

- Conducting and promoting town and country planning with a view to a correct location of activities, balanced social and economic development and the enhancement of the landscape;

- Creating and developing natural and recreational reserves and parks and classifying and protecting landscapes and places, in such a way as to guarantee the conservation of nature and the preservation of cultural values and assets that are of historic or artistic interest;

- Promoting the rational use of natural resources, while safeguarding their ability to renew themselves and maintain ecological stability, with respect for the principle of inter-generational solidarity;

- Acting in cooperation with local authorities, promoting the environmental quality of rural settlements and urban life, particularly on the architectural level and as regards the protection of historic zones;

- Promoting the integration of environmental objectives into the various policies of a sectoral nature;

- Promoting environmental education and respect for environmental values;

- Ensuring that fiscal policy renders development compatible with the protection of the environment and the quality of life.

Constitución Española, B.O.E. n. 311. Dec. 29, 1978, sect. 45 (Spain)109

Spain was the second country to recognize the right to a healthy environment in its Constitution in 1978. Section 45 of the Spanish Constitution provides:

Everyone has the right to enjoy an environment suitable for personal development, as well as the duty to preserve it.

The public authorities shall watch over a rational use of all natural resources with a view to protecting and improving the quality of life and preserving and restoring the environment, by relying on indispensable collective solidarity.

For those who break the provisions contained in the foregoing paragraph, criminal or, where applicable, administrative sanctions shall be imposed, under the terms established by the law, and they shall be imposed, under the terms established by the law, and they shall be obligated to repair the damage caused.

Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası [Constitution], T.C. Resmi Gazete No. 17863 (Nov. 7, 1982), art. 56110

The chapter of Turkey’s Constitution on “social and economic rights and duties” provides that “Everyone has the right to live in a healthy and balanced environment.”

Constitution of the Philippines (1987), art. II, § 16111

The Constitution of the Philippines provides a right to a healthy environment in paragraph 16 of the second article of the Constitution, “Declaration of Principles and State Policies”: “the State shall protect and advance the right of the people to a balanced and healthful ecology in accord with the rhythm and harmony of nature.” Notably, the right is not included in the third article setting out the Bill of Rights.

Constituição Federal [C.F.] [Constitution] (1988), art. 225 (Braz.)112

The Brazilian Constitution dedicates its fifth chapter to the environment, with Article 225 providing: “All have the right to an ecologically balanced environment which is an asset of common use and essential to a healthy quality of life, and both the Government and the community shall have the duty to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.” The rest of Article 225 lays out specific duties for the Government with respect to remedies, protected areas, inalienable lands, and nuclear power plants. The right to a healthy environment is not included in chapter I, Article 5 of the Constitution on individual and collective rights and duties.

Constitution de la IVème République Oct. 19, 1992, J.O. No. 36, Title II, Sub. I, art. 41 (Togo)113

The Togolese Constitution states in Article 41: “Everyone has the right to a healthy environment. The State ensures the protection of the environment.”

Nueva Constitución Política del Estado (C.P.E.) Feb. 7, 2009, La Gaceta (Separata) Ed.Esp. art. 33 (Bolivia)114

Article 33 of the Bolivian Constitution provides: “Everyone has the right to a healthy, protected, and balanced environment. The exercise of this right must be granted to individuals and collectivities of present and future generations, as well as to other living things, so they may develop in a normal and permanent way.”

Constituição da República de Angola [Constitution] Jan. 21, 2010, art. 39 (1) 115

The Constitution of Angola includes Article 39 (1) in its chapter on “fundamental rights, liberties and guarantees.” The article provides: “Everyone has the right to live in a healthy and unpolluted environment, as well as the duty to defend and preserve it.”

Constitution de la République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire Dec. 30, 2020, J.O. No. 82, 59th Year, Art. 21 (Alg.)116

Article 21 §2 of the Algerian Constitution provides: “The State sees to . . . assuring a healthy environment in order to protect persons as well as the development of their well-being.” This Article is part of Title I of the Constitution on “the General Principles Governing the Algerian Society” and is not included in the next Title dedicated to fundamental rights and public freedoms.

ii. National Litigation on the Right to a Healthy Environment

Kumar v. State of Bihar and Others (1991) AIR 420 (India)

The Supreme Court of India examined the plaintiffs’ action to stop two tanneries from discharging surplus waste in the form of sludge that was flowing from their production plants into the Ganges River. The pollution made the river water unfit for drinking and irrigation purposes. The Court observed that the right to life, set out in Article 21 of the Constitution, includes the right to enjoy pollution-free water and air for the full enjoyment of life. However, the Court dismissed the case for lack of standing, holding that public interest litigation cannot be invoked by a person to satisfy their “personal grudge and enmity.”

Oposa v. Factoran, G.R. No. 101083, (July 30, 1993) (Phil.)

The Supreme Court of the Philippines examined whether timber licensing permits issued by the Government deprived the plaintiffs, acting on behalf of present and future generations, of their right to a balanced and healthful ecology. The Court found that the petitioners had standing to file a class-wide suit on behalf of present and future generations. Further, the Court held that all timber licenses must be revoked or rescinded by executive action, as they did not constitute contracts, property, or property rights protected by the due process clause of the Constitution and were breaching the petitioners’ right to a balanced and healthful ecology.

Dhungel v. Godawari Marble Indus. and Others, WP 35/1992 (Oct. 31, 1995) (Nepal)

The Supreme Court of Nepal examined whether the environmental degradation of the Godawari forest caused by the marble mining industry violated the applicants’ right to life and health and caused damage to their property. The Court determined that the right to a clean and healthy environment is embedded within the right to life. The Court also noted that development is the means to live happily and that human beings cannot live a clean and healthy life without a clean and healthy environment. The Court rejected the mandamus action on the ground that it could not be issued based on a general claim of public interest in the absence of a clear statement of respondents’ legal duty.

Montana Env’t. Info. Ctr. v. Dep’t. of Env’t. Quality, 296 Mont. 207 (1999)

The Supreme Court of the State of Montana examined whether the licensing of a massive open-pit gold mine by the state Department of Environmental Quality violated the right to a clean and healthful environment guaranteed by the state Constitution. The Court applied strict scrutiny to government and private actions that implicate the right to a clean and healthful environment. The Court held that the exclusion of some activities from non-degradation review without any regard to the volume of the substances being discharged by the Minnesota Department of Environmental Quality violated the fundamental right to a clean and healthful environment.

The Federal High Court of Nigeria examined whether the gas flaring activities conducted by Shell corporation in the country violated the petitioners’ right to life and dignity and right to a clean poison-free, pollution-free and healthy environment. The Court determined that respondents carried out their activity without any regard for its deleterious and ruinous consequences, focusing on their commercial interest and maximizing profit. The Court held that the right to life and dignity of the person, including the right to a clean, poison-free, and pollution-free air and healthy environment, had been grossly violated and threatened by the gas flaring activities conducted by the respondent. The Court declared the provisions allowing gas flaring unconstitutional, null, and void.

Robinson Township v. Commonwealth, 96 A.3d 1104 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2014)

In this case, the Commonwealth Court of the state of Pennsylvania examined whether an act reforming the state’s Oil and Gas Act regarding shale gas violated the right to a healthy environment as provided by the Pennsylvanian Constitution. Article I, Section 27 of the state Constitution says: "The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania's public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come.” The court examined the scope of both sections of the Article, i.e., the description of the environmental rights of individuals and the public trust doctrine. Striking down the Act, the court held that the Act was incompatible with the state’s duty as a trustee of Pennsylvania’s natural resources. This ruling is particularly interesting in that it examines intergenerational concerns in the context of the right to a healthy environment.

Conseil Constitutionnel [CC] [Constitutional Court] decision No.2022-843 DC (Aug. 12, 2022) (Fr.)

This decision overturns prior case law (Conseil Constitutionnel, Decision No.2012-282 QPC, Nov. 23, 2012), and holds that the installation of a gas terminal would be justified only in case of “severe threat” to the energy supply. Absent such a threat, the installation of the gas terminal in question would breach the right to a healthy environment. This is the first direct application of the right to a healthy environment provided by the Charter for the Environment included in the French Constitution. The Charter provides for a right to live in a balanced environment which shows due respect for health. Earlier case law held that this right under the Charter was nonjusticiable.

D. Books on the Right to a Healthy Environment

This part lists books that discuss different aspects of the right to a healthy environment: the implementation of this right, the adoption of the right at the international level, and the “greening of human rights” jurisprudence. These books do not analyze the right to a healthy environment recently adopted by the UNGA but instead illustrate the various paths that can be explored when implementing the right to a healthy environment.

David R. Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment (UBC Press eds.) (2011)

This book, written by the current UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, discusses the increasing recognition of the right to a healthy environment and the benefits associated with this legal change. This resource offers a detailed description of the context, evolution, and definition of the right to a healthy environment, as well as a comparison of the ways this right was adopted in various world regions and legal traditions. Boyd concludes that the adoption of a right to a healthy environment has had a positive impact on environmental protection provisions and environmental performance. A more detailed, but earlier, version of Boyd’s argument is available in Boyd’s Ph.D. thesis on the same topic.117

The Human Right to a Healthy Environment (J. H. Knox & R. Pejan eds., Cambridge University Press) (2018)

This book is a collection of essays from scholars and practitioners detailing their thoughts on what is — or should be — the international human right to a healthy environment. The book challenges the absence of an internationally recognized right to a healthy environment to emphasize the emergence of the interrelation between human rights and the environment, leading to the application of human rights law to environmental issues by UN mechanisms.

Sumudu Atapattu & Andrea Schapper, Human Rights and the Environment: Key Issues (2019)

This textbook adopts a socio-legal lens to explain the interrelations between human rights and the environment. It lays out the evolution of human rights and the environment, the relevant human rights for environmental protection, the influence of climate change on human rights, and emerging issues related to environmental rights.

This manual details how the ECHR and the European Social Charter contribute to environmental protection in member states of the Council of Europe, with a specific focus on the interpretation of these human rights instruments with respect to the right to a healthy environment. This manual synthesizes the ECtHR jurisprudence on the relation between fundamental human rights and the environment and thereby implicitly upholds a right to a healthy environment.

E. Journal Articles Discussing the Right to a Healthy Environment

This part describes a selection of scholarly articles that discuss the right to a healthy environment. Most of these articles focus on how best to recognize this right at the UN level. An analysis of national provisions recognizing this right helps explain the insufficiency of relying on national or regional recognition, and thus the need for an international agreement. A conceptual clarification of children's rights and the right to a healthy environment provides useful insights on the growth of youth-focused litigation and the proposed General Comment on the rights of the child and the environment. A discussion of the green amendments in U.S. state constitutions, often including a right to a healthy environment, and a comparison of national laws with Australian law provides context for the growing lack of credibility of the U.S. and its human rights commitments.

Janelle P. Eurick, The Constitutional Right to a Healthy Environment: Enforcing Environmental Protection through State and Federal Constitutions, 11 Int'l Legal Persp. 185 (1999)**

This article examines the right to a healthy environment as incorporated into national and individual state constitutions in the U.S. The article finds several advantages to implementing a constitutional right to a healthy environment: broader standing requirements; new causes for action to enforce environmental protection; new remedies for addressing environmental problems; increased level of scrutiny applied by reviewing courts; and a check on legislative action regarding the quality of the environment. Despite being published in 1991, this article provides a good overview of the right to a healthy environment in individual states' constitutions in the U.S., which is especially relevant given the adoption of the Environmental Rights Amendment to the New York State Constitution in November 2021.118

Alan Boyle, Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next?, 23 Eur. J. Int. Law 613 (2012)

This article describes perspectives on the adoption of a right to a healthy environment at the UN level. First, the article details the interrelation between human rights and the environment, highlighting the importance of recognizing environmental human rights. Second, the article describes how UN Human Rights institutions’ reports have been increasingly linking environmental issues with human rights. Third, the article recounts the development of procedural rights in an environmental context and their interpretation by the ECtHR. The author considers whether adopting a declaration or a protocol could be an appropriate mechanism for recognizing the right to a healthy environment at the UN level. This right would then be part of the economic and social rights provided by the ICESCR. Fourth, the article examines the issue of the extra-territorial application of existing human rights treaties and challenges associated with the implementation of human rights to protection from transboundary pollution and climate change.

David R. Boyd, The Constitutional Right to a Healthy Environment, 54 Env’t.: Sci. & Pol’y. Sustainable Dev. 3 (2012)

This article by the current UN Special Rapporteur on the right to a healthy environment discusses the advantages of enshrining a right to a healthy environment in national constitutions and lists countries that have recognized this right (in their constitution, through legislation, or by signing international agreements). According to the author, the recognition of this right leads to stronger environmental laws in countries that have adopted a right to a healthy environment (in seventy-eight out of ninety-two nations at the time). Another benefit of incorporating the right to a healthy environment is an advanced screening of new laws and regulations, as they must be consistent with the government's obligation to respect, protect and fulfill the right to a healthy environment. Finally, the article describes other benefits related to the recognition of the right to a healthy environment, such as the fact that it serves as a safety net and increases public participation in policy development.

John H. Knox, Constructing the Human Right to A Healthy Environment, 16 Ann. Rev. L. & Soc. Sci. 79 (2020)

This article by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the right to a healthy environment examines the development of environmental human rights since the late twentieth century. The article categorizes this development in three ways: the recognition of environmental rights at the national and regional levels, the greening of human rights, and the development of procedural rights in international instruments. The article then considers the consequences for human rights and the environment of the adoption by the UN of an instrument recognizing the right to a healthy environment.

Rachel Pepper & Harry Hobbes, The Environment is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights, and Environmental Rights, 44 Melbourne U.L.R. 634 (2020)

This comparative law article reviews the international environmental rights regime and compares the implementation of the right to a healthy environment in specific national legal systems. The article concludes with an examination of the Australian regime, which, the article finds, is less advanced than other countries.

Ishrat Jahan, Do We Need an International Instrument for the Recognition of the Right to a Healthy Environment? 51.6 Environ. Pol.’y L. 377 (2021)

This article argues for the implementation of an international instrument recognizing the right to a healthy environment. It describes the scope of this right and the benefits of implementation. The article reviews scholarly articles, national constitutions, and regional court cases to define what the right to a healthy environment encompasses. Examining the gap between the legal recognition of this right at national and regional levels and the actual implementation of its substantive elements, the author argues that an international instrument could precisely fill this gap. He calls for an Optional Protocol to the ICESCR that would recognize the right to a healthy environment. The author argues that such an approach would be the most coherent way to recognize this right because there is already an Optional Protocol to that Covenant and the Covenant already includes some of the rights that could provide support for the right to a healthy environment.

James R. May, The Case for Environmental Human Rights: Recognition, Implementation, and Outcomes, 42 Cardozo L. Rev. 983 (2021)

This article reviews national, regional, and international provisions recognizing the right to a healthy environment. The article critiques the implementation of this right while examining the two means of implementing the right at the national level: express constitutional recognition of a substantive right or implied constitutional recognition of a substantive right. Despite numerous court decisions upholding the right to a healthy environment, the article observes that a vast majority of cases have been reversed, ignored, or forgotten. Finally, the article focuses on the effectiveness of environmental constitutional provisions related to the decrease of pollution at the domestic level.

Aoife Daly, Intergenerational Rights Are Children’s Rights: Upholding the Right to a Healthy Environment through the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1 (June 20, 2022) (available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4141475)

This article examines the intersections between intergenerational equity, children’s rights, and the rights of future generations under the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child. The article argues that the confusion among these concepts may lead to a failure to include children’s rights in climate litigation. The author asserts that intergenerational rights are children’s rights as children are present people and, therefore, have legal status, unlike future people. The author describes the principle of the best interest of the child under the Convention of the Rights of Children as the most promising route for improving climate mitigation policies.

Conclusion

The contemporary environmental movement successfully raised international awareness of the issue of environmental rights. As a result, the right to a healthy environment was recognized, in a variety of different ways, in international declarations, treaties, regional agreements, national constitutional provisions, legal cases, and soft law instruments. The recognition of the right to a healthy environment in these legal documents reflects a social and political context in which the right is progressively strengthened. The human right to a healthy environment is inextricably intertwined with other human rights, especially the right to life, the right to private and family life, the right to water and adequate sanitation, the right to food, the right to housing, and the right to reach the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Enforcing the right to a healthy environment would reinforce all of these associated rights. This guide is a starting place. Further research and advocacy dedicated to the right to a healthy environment will help with the critical work of defining, publicizing, implementing, enforcing, and achieving this right.

Annex I

International Bodies Working Directly or Indirectly to Advance the Right to a Healthy Environment

This section lists international organizations involved directly or indirectly in advancing the right to a healthy environment. The interdisciplinary nature of this right explains the wide range of relevant organizations at the international level.

- UN Bodies Working Directly or Indirectly to Advance the Right to a Healthy Environment

United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC)

The HRC is the main intergovernmental body in the UN system responsible for strengthening the promotion and protection of human rights. The HRC can engage UN special procedures which are mechanisms established by the Council to gather expert observations and advice on worldwide human rights issues. The HRC recognized the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment in October 2021.

United Nations Human Rights Committee (Human Rights Committee)

The Human Rights Committee is a body of independent experts monitoring the implementation of the ICCPR by State parties. The Human Rights Committee drafts General Comments interpreting the ICCPR. In General Comment No. 26 on the right to life, the Human Rights Committee referenced the impact of climate change, environmental degradation, and unsustainable development on future generations’ enjoyment of the right to life.

United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)

The CESCR is a body of independent experts monitoring the implementation of the ICESCR by State parties. General Comments regarding the ICESCR, drafted by the CESCR, have referenced the right to a healthy environment as implied in economic, social, and cultural rights.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

The CRC is a body of independent experts monitoring the implementation of the Convention on the Right of the Child and the Optional Protocols to this Convention. The CRC issued General Comment No.7 on the implementation of child rights in early childhood, which acknowledges a healthy environment as an indispensable condition for the realization of human rights in early childhood.

United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP)

The UNEP is the global agency that sets the environmental agenda and promotes the implementation of sustainable development. The UNEP is the leading environmental authority within the UN system. It seeks to strengthen environmental standards while ensuring the implementation of existing environmental protections.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

The IPCC is the UN body in charge of assessing the science related to climate change. The Panel publishes reports that serve as a basis for international negotiations on climate change and national public policies and promote international awareness of climate change. IPCC reports are drafted by scientists and evaluated by governments. IPCC reports are a continuous source of relevant information on changing ecosystems and climate.

World Health Organization (WHO)

The WHO is the UN agency in charge of promoting health and cooperation among nation States. The WHO insists on environmental health, noting that 24 percent of global deaths are linked to the environment. WHO also directs attention toward various component of the right to a healthy environment: clean air; a stable climate; adequate water, sanitation and hygiene; the safe use of chemicals; and sound agricultural practices.

- Other International Bodies Working Directly or Indirectly to Advance the Right to a Healthy Environment

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

The IUCN is a union of governments and civil society organizations that aims to conserve nature and accelerate the transition to sustainable development by encouraging international cooperation and providing scientific knowledge to guide conservation.

Global Environment Facility (GEF)

The GEF is the largest international trust fund focused on projects aiming to improve the environment. It provides support to government agencies, civil society organizations, private sector companies, and research institutions.

Annex II

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment: Right to a Healthy Environment: Good Practices, HRC, 43rd Sess., A/HRC/43/53 (December 2019), Annex I119

* Solène Kerisit is a Master’s Student in Public Economic Law at Sciences Po Law School and Martha Davis is a University Distinguished Professor and Co-Director of the Program on Human Rights and the Global Economy at Northeastern University School of Law

1 See G.A. Res. 76/300, The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment (July 28, 2022). This follows the United Nations Human Rights Council’s adoption in October 2021 of Resolution 48/13 recognizing the human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. Human Rights Council Res. 48/13, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/Res/48/13 [hereinafter HRC Res.]. Annex I describes international bodies that are working on the right to a healthy environment.

2 Majorities in Most Publics Surveyed See Climate Change as a Very Serious Problem and Think Their Government is Doing Too Little to Address It, Pew Rsch Ctr. (Sept. 21, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/29/concern-over-climate-and-the-environment-predominates-among-these-publics/ps_2020-09-29_global-science_03-01/.

3 John H. Knox (Special Rapporteur), Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, ¶ 37, U.N. Doc. A/73/188 (July 19, 2018).

4 Katarina Zimmer, A Healthy Environment as a Human Right, Knowable Mag. (Apr. 20, 2021), https://knowablemagazine.org/Article/society/2021/a-healthy-environment-human-right.

5 See Knox, supra note 3, ¶ 30; see also Constituição da República Portuguesa [C.R.P.] [ Constitution ] 1976, art. 66 (Port.).

6 See Knox, supra note 3, ¶ 30; see also Constitución Española [ Constitution ] Oct 31, 1978, art. 45 (Spain).

7 See U.N. Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm Declaration, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1 (June 16, 1972).