By Christian I. Bale

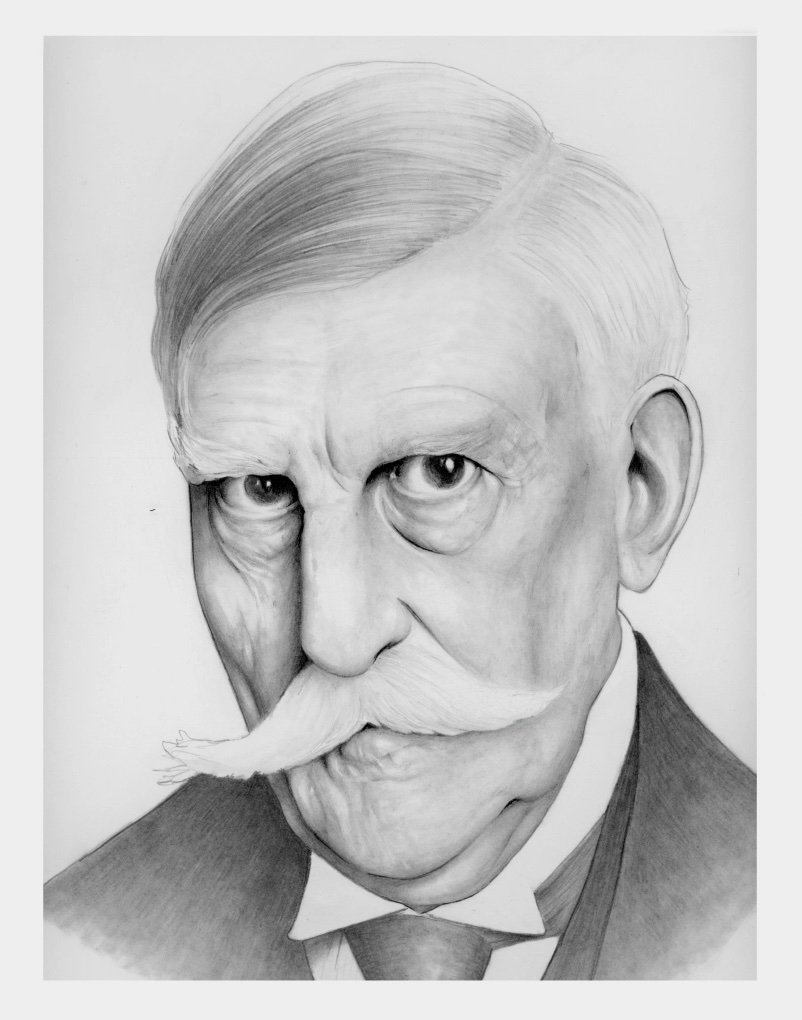

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Artwork by Matthew G. Schafer, friend of the author.

Freedom of speech is like baseball, hotdogs, and apple pie. Whereas one survey found that less than half of Americans can name the three branches of the federal government, another showed that 64 percent of Americans can recall that the First Amendment protects free speech.

Despite its familiarity, modern free speech doctrine is considerably untethered to the First Amendment’s text or the founding generation’s understanding of expressive freedom. Now, because of that constitutional vulnerability, and after nearly a century during which the concept of free speech has expanded, the doctrine may be on the precipice of contracting as the public—and at least two members of the Supreme Court—have indicated a willingness to revisit First Amendment precedent.

The First Amendment in the Twentieth Century

Perhaps the most prominent theory animating modern free speech doctrine is that robust speech protection cultivates a “marketplace of ideas.” Like the concept of an economic free market, the marketplace theory holds that the best way that a society can discern truth is by putting ideas into competition with other ideas.

The marketplace theory flourished in the twentieth century when today’s First Amendment scholars and members of the Supreme Court came of age. To the current guard of academics and jurists, it must have seemed that what counted as speech under the First Amendment was constantly expanding. Early in the century, the Court had held that the freedom of speech did not extend to motion pictures, but in 1952, the Court ended censorship of the big screen. And whereas the Court had previously ruled that advertisements were not speech for First Amendment purposes, it changed course in 1976. Alongside numerous other examples, the evolution seemed to suggest that unrestricted expression is the American way.

Even stare decisis has not stood in the way of the march to robust speech protections. Latin for “let the decision stand,” stare decisis is the judicial doctrine that once a court has answered a legal question, that decision will govern future comparable legal questions. Adherence to stare decisis means that judges who would not rule a certain way in the first instance will refrain from overturning an established precedent.

Yet, in a 2017 law review article, Professor Randy Kozel explained that twenty-first century First Amendment innovations—much like those of the century before—reflect “a specialized, and diluted, version of stare decisis that applies to situations in which precedent threatens to interfere with expressive liberty.” Among Kozel’s examples include United States v. Stevens, in which the Court abjured its past endorsements of balancing the value of speech protections against societal costs, and United States v. Alvarez, in which the Court distanced itself from its previous statements about the worthlessness of false speech. In Kozel’s words, the Supreme Court “has treated robust expression as more important than legal stability.”

Flimsy Constitutional Foundation

Robust protection for speech might seem like the American way, but one will not find language relating to the marketplace of ideas in the text of the Constitution, nor from any record about the public meaning of the First Amendment at the time of ratification. The text states simply, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech . . . .” One might argue that the words “no law” denote an absolute prohibition on the government from regulating speech, but since the founding, we have recognized various implicit limitations to the categorical text of the First Amendment. For example, a year after the First Amendment’s ratification, 13 of the 14 states had laws imposing criminal liability for defamation. Other familiar limitations are incitement, obscenity, and true threats. As the Court explained in Roth v. United States, “the unconditional phrasing of the First Amendment was not intended to protect every utterance.”

Originalism, likewise, does not account for modern free speech doctrine. Originalism posits that one should interpret the text of the Constitution according to its original public meaning. From famous founding-era documents, we know that the framers valued freedom of thought. For instance, James Madison, in the Memorial and Remonstrance, opposed state-established religion. In Madison’s view, even “three pence” of support for the church was a slippery slope towards religious tyranny. Additionally, both Madison and Thomas Jefferson argued that the Sedition Act of 1798 was unconstitutional. Madison and Jefferson went as far as contending that the states could nullify the federal censorship law because it usurped the states’ police powers.

The founders, however, were not the speech libertarians that we are today. Most commentators at the time—including Justice Joseph Story in his famous Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States—understood the First Amendment to bar “prior restraints” on writing and speech. By contrast, the Constitution was not widely thought to protect against after-the-fact punishment in response to what people wrote or said. This conception of the First Amendment traced its roots to the English principle of freedom of the press, a common law rule that William Blackstone articulated in his Commentaries on the Laws of England.

The marketplace of ideas theory is of a more recent vintage. The earliest articulation comes from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s famous dissent in Abrams v. United States.

Holmes wrote:

“Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition . . . . But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas . . . . The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

After explaining the rationale behind the marketplace of ideas, Holmes added: “That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.” But Holmes’s pronouncement had little basis in the Constitution’s text or its original public meaning.

Rather, the marketplace rationale was the brainchild of the British philosopher John Stuart Mill, and it was not always a viewpoint with which Holmes agreed. Just months before writing his dissent in Abrams, Holmes authored three majority opinions upholding criminal convictions in free speech cases. But on the suggestion of a friend, Holmes revisited On Liberty, which led him to believe that free speech should extend beyond Blackstone’s view.

In the essay, Mill offers four reasons for protecting speech. First, opinions that are presently unpopular may later turn out to be true and become widely accepted. Second, an opinion that is erroneous on the whole may contain a portion of the truth. Third, even if popular opinion is “true,” society might not understand why it is true unless people are free to challenge its underlying rationales. And fourth, without open debate, an accepted truth could become an empty dogma or “a mere formal profession.”

The American Civil War may have primed Holmes to adopt Mill’s defense of free discourse, which was grounded in the pursuit of truth. Over the course of the war, Holmes was wounded three times, nearly died from dysentery, and endured the deaths of close friends. When Holmes wrote of “fighting faiths,” he knew firsthand of the lengths some might go to defend their worldviews. He also acknowledged that the passage of time and the evolution of human thought tended to disprove ideas that people had previously held so dear.

Whatever his motivation, as Professor Thomas Healy has observed, Holmes adopted Mill’s defense of free speech in his Abrams dissent “almost verbatim.” Although people must make assumptions about the world in order to take actions and live their lives, Holmes found convincing Mill’s view that society should not assume truths for the purpose of suppressing speech. The justice’s about-face, then, was motivated by philosophical considerations, not legal discernment. Rather than emanating from the First Amendment, the marketplace of ideas springs from an ethos of epistemic humility. Holmes may have been the one to introduce the theory into our constitutional tradition, but his declaration has proven to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A Generational Shift and a Constitutional Change?

Fast forward a century, and perhaps the greatest existential threat to the United States is not a physical war, but a war on truth. The phenomenon of misinformation—and deliberate disinformation—seems to infect nearly every politically salient issue. This has led some legal commentators to contend that the marketplace of ideas has either become distorted or is itself a vehicle for distorting truth. They suggest that in another day and age, it may have been useful for society to submit contentious ideas to the wisdom of the masses. But today, when demagogic leaders can leverage social media to propagate “alternative facts,” the free market of ideas requires some regulation.

A growing proportion of the American public seems to agree. According to an August 2021 PEW Research Center Survey, 48 percent of American adults now believe that the government should restrict false information, even at the cost of losing some freedom to access and publish content. That figure is remarkably higher than in 2018, when 39 percent of Americans favored government-imposed speech restrictions. The change is even more pronounced within the Democratic Party. Sixty-five percent of those who identify as Democrats now favor such restrictions, a dramatic increase from just 40 percent in 2018. Fortunately for hardy free speech advocates, the public does not propound authoritative constitutional doctrine.

Rather, that is the province of the Supreme Court. But the high court has signaled that it might change course starting with New York Times v. Sullivan, the 1964 landmark decision that set a high bar for winning libel suits against the press. Justice Clarence Thomas has long called for reversing Sullivan and its progeny, maintaining that they were “policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.” Justice Neil Gorsuch, who demurred on stare decisis grounds when he was asked at his confirmation hearings about revisiting Sullivan’s actual malice standard, recently expressed his frustration with the ascent of false information in a July 2021 dissent. He explained, “[w]hat started in 1964 with a decision to tolerate the occasional falsehood to ensure robust reporting by a comparative handful of print and broadcast outlets has evolved into an ironclad subsidy for the publication of falsehoods by means and on a scale previously unimaginable.”

Justices Thomas and Gorsuch may not be alone in their hope to scale back protections against defamation suits. Although the Sullivan opinion was limited to publications about “public officials,” subsequent decisions broadened the protection to “public figures,” a category that includes celebrities and those who have spoken on topics of public concern. As Adam Liptak has noted, in a 1993 book review, Justice Elena Kagan—at the time, a law professor at the University of Chicago—expressed her view that the later decisions were “questionable extensions.”

For the remaining 50 percent of Americans who favor strong speech protections, they will have to contend with the fact that their preferred reading of the First Amendment is not rooted in the text or the original meaning of the Constitution. As Fourth Circuit Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson explains (without endorsing the theory), one of originalism’s virtues is that it provides principles that judges can apply neutrally without regard to personal preferences. The originalist critique, then, of other constitutional theories about the First Amendment is this: if the theory is not grounded in the original understanding of the document, in what, exactly, is it grounded?

Holmes rooted his theory of the First Amendment in epistemic humility, but one may reasonably challenge the legitimacy of a constitutional interpretation based in Millian liberalism. If a judge applies philosophical principles to constitutional analysis, there is the possibility that a different judge who endorses a different set of philosophical assumptions will disagree with the extant—but apparently free-floating—animating theory undergirding a constitutional doctrine. Unconstrained by external criteria, constitutional decision-making becomes individualistic, judicial supremacy.

Although this Court may not be the one to retheorize the First Amendment, a new generation of lawyers may seek a different path. Echoing Justice Holmes, we free speech apologists might protest: “That . . . is the theory of our Constitution [!]” But if stare decisis has given way when laws burdened expressive liberty, perhaps precedent is equally malleable if society comes to believe that the marketplace of ideas no longer serves its intended purpose: the search for truth.

Christian I. Bale (@ChristianIBale) is a lawyer in Wilmington, Delaware, and former member of the Duke Law First Amendment Clinic. His writing has appeared in the Washington Post, The Hill, the Duke Law Journal, and the Yale Journal on Regulation. Thank you to the Northeastern Law Review’s excellent editors, especially Christine Raymond and Aly McKnight, for their feedback and edits.