How Can Communities of Color Access Promised State Reforms When the Department of Corrections’ Silence on Historic Inequalities Continues to Serve as a Barrier?

Mac Hudson

Am I any less human because I happen to be Black and in prison? Are Massachusetts prisons the only place on Earth that racism does not exist? There isn’t anyone in America that hasn’t heard the name George Floyd and the many names of Black and Brown lives prematurely extinguished at the hands of police. It has created a difficult national conversation that has brought society full circle to confront one of America’s ugly realities of racial oppression and racial inequity. Our society has had to face a few hard truths that have given way to the idea that no citizen is privileged to sit idly by and permit such inhumane treatment without suffering a collective consequence to their own moral decadence. Booker T. Washington said, “one man cannot hold another down in the ditch without staying down in the ditch with him.” Morally speaking, racism has generationally kept all of us, people of all races, down. It has become so ingrained in society that it is as American as apple pie! So much so, that when someone attacks racism, some white people think you are attacking America herself or her ideals instead of challenging Americans to live up to her ideals.

The desire to eradicate this disease has unified a rainbow coalition of outrage that has created and moved white allies to publicly stand against racism. The Black Lives Matter movement has steadily maintained a beating drum of frustration that harkens back to slaves on the plantation, and presently generationally echoes those same despairs in the business world, Black social and political organizations, Black churches, or on the streets of our cities.

Its vibration reverberates behind the prison walls to also include those confined therein. Other state correctional agencies have recognized this fact, such as Suffolk County Sheriff Steven Tompkins who publicly acknowledged and denounced systemic racial oppression of Black and Brown citizens and the disproportionate sentences of these ethnic groups compared to white citizens.

The Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) has been conspicuously silent on the Black Lives Matter movement, or if systemic racial oppression exists behind its walls. The DOC’s goal is to stay out of the spotlight rather than share in the heavy lifting that is being conducted at all four corners of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in hopes that the question of whether Black lives matter will eventually die out in the news cycle to prevent its agency from having to take a position. These kind of deliberate hide the ball tactics give new meaning to the phrase, “white silence is violence.”

Prison is a microcosm of society at large. It’s riddled with the same racial biases, hostilities, and inequalities that are played out through Departmental policy and practices which adversely impact incarcerated communities of color. The Department of Corrections’ head officials and prison administrators statewide are predominantly white with little to no experience with other ethnic groups’ cultures or religious observances. It is these blind spots that have led to a subculture of indifference that has formed itself into a hardened racial caste system over the years—one in which Black and Brown prisoners have to negotiate their own humanity, no different than their shared experiences in society, in order to receive guaranteed state reforms promised to all prisoners or basic human decency. In the movie “Heat of the Night,” Sidney Poitier’s Detective Mr. Tibbs threatens Ms. Cilicy Tyson with what is commonly known about imprisonment for Black people. He said: “There’s white time and then there’s color time, and color time is the worst!”

This remains true today. When a Black or Brown prisoner seeks or obtains meaningful access to rights or privileges, Administrators or Departmental policymakers respond with more adverse policies to malign access or underserve that community. Or, there is the kind of retaliatory vindictiveness that says plainly, “you have no rights that I’m willing to recognize.”

A glimpse of this is seen in the case of a prisoner who brought suit against the DOC for his removal from the religious diet list for having missed three meals. The United States District Court determined in Denson v. Marshall, 44 F.Supp.2d 400 (D. Mass. 1999) that this violated the prisoner’s constitutional right to adhere to his religious dictates. In return, DOC Director of Program Services Jaileen Hopkins created a new policy that singled out religious diets, requiring that a prisoner be given a disciplinary report for any missed meals and charged restitution. No such requirements exist for medical or regular diet meals.

In another instance, in response to the growth of cultural educational events such as Kwanzaa, Black History month, and Juneteenth—and growing community interest in these events—Director Hopkins recently passed a policy that limits all special cultural and religious events to five outside community guests. These events have been largely successful and without any security incidents, but have been reduced with no meaningful explanation. Other than, because we say so!

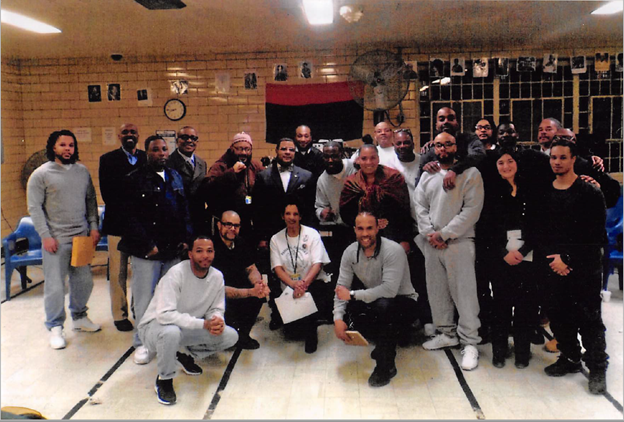

Image Description: Black History Month Event at MCI-Concord with keynote speaker Massachusetts District Attorney Rachael Rollins, dated February 2019.

This kind of arbitrariness seeks to enforce those rules and procedures favorable to administrators and the officers’ union, while disregarding, completely, those rules, procedures, and laws that are favorable to the prisoner. These include access to lower security facilities prior to release and receipt of those educational and reparational initiatives to reconnect with their respective communities and, more importantly, to themselves, so that prisoners will see themselves as contributors to rather than alienated from those communities. By the time the prisoner obtains access to those entitlements or benefits, they are virtually out the door. This has led to a recent cultural clash in the DOC that sparked several litigation actions fighting for cultural education, adequate accommodations for related cultural and religious observances granted through DOC’s own self-improvement policies and religious Handbook manual in Hudson v. Chmiel, No. 1581-cv-02953 (Mass. Super. May 11, 2015) and Hudson v. Spencer, No. 15-2323, 2018 WL 2046094, at *5 (1st Cir. Jan. 23, 2018).

These kinds of disparities have been routinely brought before the court by Massachusetts’s prisoners of color seeking adequate program accommodations or religious practices or diets that differ from mainstream Christian views or the dominant white cultural observances over the last thirty years.1 The plethora of cases where Massachusetts Courts have admonished the DOC have not made the Department more culturally tolerant of these differences but more resistant and resentful. This causes frequent court intervention from new litigation.2

It is in this backdrop that I’ve decided to publish these two public letters to administrators raising the racial disparities endured by myself and others. I am seeking to address the racially oppressive conditions to bring about a productive discussion and solutions. Unfortunately, my correspondences have been met with much of the same resistance and circular reasoning that attempts to sidestep the Black and Brown experiences in DOC’s custody. These inept replies can only be attributed back to the non-stance taken by the DOC Commissioner on the initial question that our country is in the midst of grappling with. Do Black Lives Matter? The Department’s total silence sends a dual message: Black lives do not matter in the Department of Corrections and the governing rules are written in pencil when it comes to communities of color.

On February 3, 2004, former Secretary of Public Safety, Edward Flynn said during the defrocked priest John Geoghan’s murder investigation: “If nothing else, inmates must leave our custody with a belief that there is moral order in their world. If they leave our custody and control believing that the rules and regulations do not mean what they say they mean, that rules and regulations can be applied arbitrarily or capriciously or for personal interest, then we will fail society, we will fail them, and we will unleash people more dangerous than when they went in.”

These words ring true today. Therefore I am asking all of those that support the BLM movement to join in our chorus to encourage the DOC Commissioner and administrators to take a public position on BLM and to conduct a symposium at MCI-Concord with the communities of color to address the systemic racially oppressive policies within the prison. For more on this subject, you can contact me at writeaprisoner.com.

Mac Hudson is a prison activist and jailhouse attorney for equal rights, cultural and religious education and community reparations at MCI Concord prison. He has been incarcerated since the age of seventeen and is innocent of the crime for which he has served thirty-one years. He is a board member of Prison Legal Services. Mr. Hudson works alongside Attorney Latoya Whiteside in PLS’s Racial Justice Project to identify and address discriminatory treatment and systemic racial inequities within the DOC. The Racial Justice Project is in response to decades of racial oppression complaints made by current and former prisoners. Hudson also contributed to the documentary “Voices from the Behind the Wall,” the accompanying anti-violence curriculum, and an inmate-directed educational film. Hudson is studying for a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts, Culture and Media Communication at Emerson’s Prison Initiative. Hudson believes that self-awareness is community awareness, and community awareness creates a universal consciousness that sparks change in the world.

Editor’s Note: The NULR is proud to present these open letters, originally sent to the addressed recipients in June 2020, in their original and unedited form in order to preserve the unique voice and intent of the author.

1 Manor v. Superintendent of MCI-Cedar Junction, 416 Mass. 820 (1994) (order to allow Black prisoners to wear African National Medallion as a political expression); Hudson v. Marshall, No. 00-4412 (Mass. Super. 1998) (superintendent abused discretion in disallowing 10 religious books per person in segregation); Matthew v Dubios, No. 94-P-1274 (Mass. Super. 1995) (order to allow Muslims in segregation watch access to make prayer); Ali v. DuBois, No. 951614, 1996 WL 1185051, at 1 (Mass. Super. Sept. 24, 1996) (denial of Ramadan meal to Nation of Islam prisoner unless he converted to orthodox Islam violated his constitutional rights); Trapp v. Dubois, No. CIV.A.95-0779B, 2000 WL 744357, at 3 (Mass. Super. May 8, 2000) (order for prisoner accommodation for Indian religious practices); Abdul-Alazim v. Superintendent, Massachusetts Corr. Inst., Cedar Junction, 778 N.E.2d 946 (Mass. App. Ct. 2002) (order to allow prayer, Kufi, and prayer book in Department of Disciplinary Unit); Gordon v. Pepe, No. CIV.A.00-10453-RWZ, 2004 WL 1895134, at 6 (D. Mass. Aug. 24, 2004) (order to provide Rastafarian religious diets in accordance with his religious dictates); Ellis v. Dennehy, No. 1:05-CV-11221 (D. Mass. 2006) (settlement of religious diet meals and religious practices for members of Nation of Gods of Earths); Rasheed v. Commissioner, 446 Mass. 463 (2006) (denial of Nation of Islam practices, and dietary mandates); Cruz v. Superintendent of Old Colony Correctional Center, No. 06-cv-11924-NGM (D. Mass. 2007) (settlement to obtain a volunteer for Spanish United cultural program and allowance of cultural observance of three wise men); Hudson v. Dennehy, 538 F. Supp. 2d 400 (D. Mass. 2008), judgment entered, No. CIV.A.01-12145-RGS, 2008 WL 1451984 (D. Mass. Apr. 11, 2008), aff’d sub nom. Crawford v. Clarke, 578 F.3d 39 (1st Cir. 2009) (order to permit halal meals and human access in segregation); Yeboah-Sefuh v. Clarke, No. 08-10494- MLW (D. Mass. 2009) (order allowing Buddhist practices and dietary meals).

2 See Lebaron v. O’Brien, No. 15-00275, 2016 WL 5415484, at 21 (Mass. Super. June 15, 2016)(recognizing right of volunteers to conduct Messianic services and receive holy diet and to observe holy holidays with approved volunteers); Lebron v. Spencer, 527 Fed. Appx 25 (2013) (order for group prayer, kosher diet, and religious material in MCI-Souza Baranowski Correctional Center); Cruz v. Collins, 46 N.E.3d 114 (Mass. App. Ct. 2016) (holding plaintiffs stated claim for violation of religious rights where denied access to religious Islamic daily group prayer in designated area at MCI Gardner); McGee v. O’Brien, 160 F. Supp. 3d 407 (D. Mass. 2016)(alleging prison failed to provide Nation Gods of Earth with volunteers, corporate worships and dietary at MCI Norfolk); Trapp v. Roden, 41 N.E.3d 1 (Mass. 2015)(denial of access to Indian religious material and ritual ceremony at MCI SBCC violated prisoners’ religious rights); Skandha v. Spencer, 75 N.E.3d 1148 (2017) (grating summary judgment for prison where plaintiff alleged failure to provide religious diet); Hudson v. Spencer*, No. 15-2323, 2018 WL 2046094, at 5 (1st Cir. Jan. 23, 2018)(holding plaintiffs demonstrated religious rights violated by prison’s failure to provide adequate accommodations for jumuah group prayer or access to video and access to time and space to perform daily ritual group prayer at MCI-Concord).

OPEN LETTERS TO MCI-CONCORD

Mr. Michael Rodrigues

Superintendent. June 12, 2020

P.O. Box 9106

Concord Ma. 01742

Re “8:46” at MCI Concord

Dear Mr. Rodrigues,

Please find enclosed my recent correspondence to Ms. Jailene Hopkins, which is an continual question that I now pose in this open letter to you…Does Black Lives Matter at MCI Concord?

I ask this sincere question in light of MCI Concord white administrators do not believe or have been unwilling to confront their own implicit biases, when providing the basic minimum constitutional standards of living in a way that creates racial disparities towards Blacks and incarcerated communities of color. A question lingering from previous letters to your office , as the top administrator in and around adequete programs and accommodation needs for Blacks . I refer you to my December 27, 2017 and June 25, 2018 correspondences addressing some of these discriminatory practices. The latter complaint prompt the question then “what is it about Black cultural and religious events that bother you all, so much so, that you deny more people to participate, when having the ability to do so?” This unwillingness to address the white elephant in the room ( no pun intended) has maintained institutional racism, and fashions a false belief that you and those administrators are immune…However that immunization for me amounts to “8:46” at MCI Concord.

Today there is a national acknowledgement that two Americas exist: a White and Black one. The grayish areas in between has been the deepening acceptance or indifference by all ethnicities and whites to this truth. Calls to make “One America for all has led to the very open and honest public discourse on the matter of systematic oppression of Blacks and racial inequities that has and continues to shatter white silence. The reverberation of that shatter has led to Boston Mayor Marty Walsh to declare “Racism” as a Public Health emergency, echoing Somerville Mayor Joseph Curtatone’s declaration a week ago. Governor Charlie Baker announced in response to Mayor Walsh’s public statement, that the issues of systemic oppression of Blacks in the criminal justice system, housing, policing, and education or opportunities are real! I believe that this open, honest and uncomfortable conversation has to occur in the penal institutions that are a part of the criminal justice system in furtherance of the goal of “One America for all.”

As an incarcerated Blackman for over 30+ years inside the DOC, I have personally experience and witness other prisoners of color routinely discriminated against in every aspect of our institutional lives. From programming, classification, visits, medical, housing, religious access, and meals. There has been a great reluctance and a closing of ranks to prevent meaningful resolve even in cases that requires basic human dignity, such as permitting officers to refuse to close cell door request to use the bathroom in private on the 3-11 pm shift. Forcing a man to defecate out in the open is dehumanizing to the senses and is a vulnerable position in a prison setting. Nonetheless, this inhumane unprecedented practice is permitted to appeased the very white officers that started it to act out these personal biases against Blacks and Latino prisoners. These experiences conveys to me…Black lives don’t matter in the DOC.

Although many Black men have died in the DOC under the same suspect conditions previously before John Geoghan. Their Black mothers’ cries and pleas for justice went ignored. It was the murder of a white priest that sensationalized Massachusetts’s prison reform. That said to me…Black lives don’t matter unless its connected to white tragedy.

The same white tragedy that allow for former Public Safety Officer, Kevin M Burke to apologize to a Seattle, Washington, White community for a senseless murder of a white woman by a white inmate released from the DOC. While synchronously dismissive of the local Black communities that experiences the same senseless lost committed by black prisoners released from the DOC…all which says Black lives don’t matter.

Even when I and other prisoners of color attempt to access those State reforms promised to all inmates. When we pick up the worn out tools to rebuild ourselves to become a “Community of Self,” and reestablish connections with our respective communities that we derived from. I’ve experience White administrator such as yourself, impose unnecessary, burdensome, obstacles, conditions, or severe limitations to deny equal access or adequate accommodations to Blacks. Most which deviates from Department’s own standards. When I still prevail, despite those strenuous conditions, then sudden amnesia sets in or the rules change, scores smudged, and the goal post moved further back…What kind of message do you think that sends?

When I exercise the avenues afforded to inmates through grievances or complaints to address these racial barriers. There is an administrative suppression and disconnect from these truths. That denys myself and similar situated prisoners the ability to be meaningfully heard. Because it requires you and other administrators to see beyond their own blindness caused by white privilege. Instead, I’m told that I should be appreciative to receive the bare minimum rather than the full service promised under the State’s reforms. I am asked to grow into this kind of second class acceptance, which I outright reject. In doing so, I have been considered everything other than, desiring to be my natural Black self!

The Department of Corrections received its name change from Department of Prisons in the 1972 Omnibus Rehabilitation Act. The legislative mandate was to focus on rehabilitation. In accordance with that goal, the DOC adopted the word “inmate” over “prisoner”, and replaced the term “prison” with “facility”. These changes were to reflect that these facilities are to function in a secure “residential treatment capacity”. However, “corrections” for Black, Brown and Yellow prisoners have meant the continued over policing, heighten surveillance, exacerbation of physical and emotional trauma, and suspicious treatment, that they experienced in society. Reasoned by the same racial bias constructs and serves to deprived them of the simplest self autonomy guaranteed at mediums and lower security facilities. We have been treated as “prisoners,” and not “inmates” as the word is originally defined. So much so, that now the term “inmate” has a negative connotation amongst the general population.

I am sure that you or other White administrators do not see yourselves in this light. But this is exactly the point. You know nothing or very little about Black reality which is undergirded by those personal implicit biases. So how can you personally grasp, Blacks rehabilitation needs are different than their White counterparts. More importantly, are equally important and deserving of attention. In that vein, I propose a symposium be held at MCIConcord between your top administrators and the incarcerated prisoners of color on the question of institutional racism experience here. The first meetings should focus on the opportunity to hear from us without judgement or opinion. With the goal of identifying behaviors, policies, and practices that attributes to racial inequities. The second series of meeting should address strategies and timelines to end or change these practices or behaviors.

Thank you for your attention in this matter. I look forward to reply and hope together we can cross over on the right side of history.

Sincerely

Mac Hudson

Ms Jailene Hopkins,

Director of Program Services. June 10, 2020

50 Maple St. Suite 2.

Milford Mass. 01757

Re: Your June 5, response.

Dear Ms. Hopkins,

I received your response on June 9, 2020, regarding my May 18, 2020 complaint to Commissioner Carol Mici over the discriminatory effects if the September 2019 DOC Standard Guidelines and Time Requirements for Inmates Program Special Activities. Given your reply, I am left with the very series question of how do Top officials confront a problem, that they do not believe exist? Or if those very few acknowledged its existence, that acknowledgement stops at the door of the Department of Corrections.

So I am writing you this open letter in hopes to invite you to step back for a moment. To listen without judgement or preconceived notions about myself in order to try to understand how policies like these contribute to ongoing racial inequities and continual racial generational trauma experienced by people of color inside Massachusetts’s prison system.

I like to first acknowledge a couple of things. I understand that you as a white person born into a world of white privilege ( something that you didn’t ask for) presents certain challenges in identifying or relating to complaints like mines. Largely due to the feeling that’s its a personal attack rather than a real structural problem that existed in the Department of Corrections long before you or I. I also understand that by the mere fact if your whiteness has inoculated you and other white administrators to the real life challenges and needs of Black people in and out your custody. If our experiences are not the same in America then how can the remedy be the same? It is this great disconnect that is behind a series of administrative decisions fueled by indifference towards others that do not share in your experience or cultural practices.

Presently, Ms. Hopkins, the world is having this hard conversation about the systematic racial oppression of Blacks and experienced racial inequities that exist today. Every entity or agency from Military, NFL to the Suffolk County Sheriffs office is currently self examining their own institutional blindness caused by white privileges, racism and the othering process that takes place in America. In doing so, they have acknowledged and denounced the systematic oppression of Black life and police brutality. Merriam Webster dictionary released a

statement of its intent to revise the definition of racism to include: the exercise of that superiority belief in a systematic way that harms another people. Its now time for the Department of Corrections to also lean into this national conversation about racial disparities against Blacks inside the Massachusetts’s prisons that prevents officials from achieving the mandate of preparing each person to exercise his/her citizenship upon release.

Ms. Hopkins, this policy does violence to Black cultural and religious observances for the reasons expressed in my previous letter to Ms. Carol Mici. To say the policy applies across racial spectrums, when its primarily these Black orientated special events that routinely occurs and growing throughout the Department, renders the claim meaningless. It implicates a selective targeting of special activities as the intended goal, while concealing the motivating implicit biases. Example of the latter is seen in the exempted activities. What makes the workshops or retreats more valuable than Black cultural or religious observances, that these program special activities can have no limit set on their number of volunteers? What makes these program’s special activities more therapeutic than the Black cultural and. religious observances? And to whom exactly?

Elie Weisel, a Holocaust survivor said: “The opposite of love is not hate, its indifference; The opposite of beauty is not ugliness, its indifference, the opposite of faith is not heresy, its indifference, and the opposite of life is not death, but indifference between life and death.”

It is this indifference that I am addressing in the creation and execution of such policies and practices like these. That says to me and other prisoners of color that we’re of no value! Our Black cultural or religious observances are not equally important as Jericho circle workshops. It is not equally as important for Black volunteers to show up in numbers to support these rehabilitative and reparational initiatives. It conveys a sentiment that Black lives

don’t matter in the Department of Corrections, while you pay lip service to neutrality.

So I urge you Ms. Hopkins, to rescind this policy practices. I also encourage you to meet with the prisoner’s of color at MCI Concord to began a dialogue about practices and policies that I’ll effect our transition and rehabilitation. To acknowledge our reality that is different than your own and work towards a more inclusive solution.

I thank you for your time and patience. And look forward to your reply.

Sincerely

Mac Hudson